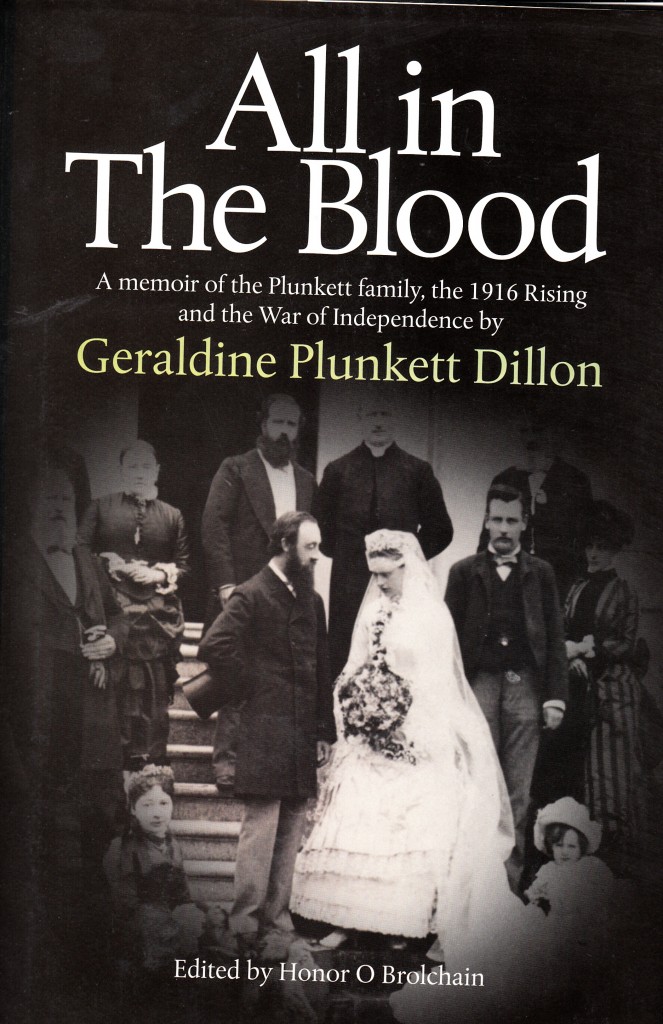

A memoir of the Plunkett Family, the 1916 Rising and the War of Independence

By Geraldine Plunkett Dillon

Edited by Honor O Brolchain

A&A Farmar 2006

aafarmar.ie

(See below for a short biography of Geraldine Plunkett Dillon)

Preface from ALL IN THE BLOOD

My grandmother, Geraldine Plunkett Dillon, who was born in 1891 and died in 1986, lived with us from the time I was very small and, long after she died, a conversation with my mother in 1997 made me realise that a huge story, part of which I had always known because I had grown up with it, was being lost. I arranged some recording sessions with my mother, a great and articulate talker, but after only the third session her last illness was diagnosed and she died a few months later in 1998. My sisters, Barbara and Ester and my brother, Fiacc, kindly gave me all the archival material in the house which included a large plastic sack of papers which had been put away and forgotten before my grandmother went into a home three years before she died. Among these were a set of ten spiral-back copybooks, the story of her ancestors, her family and her life from 1820 to the early 1920s with a wealth of description of her home and upbringing, life with her brother Joe (Joseph Mary Plunkett) and her own experiences in 1916. These copybooks date from the early 1950’s and from these and her research work from newspapers, commissions, legislation, reports and exhaustive correspondence with friends, historians and activists of the time, she was working towards the publication of a book with Anvil Press for 1966. The project fell through but that considerable body of work survived.

Geraldine Plunkett Dillon – from her introduction to her unpublished book on the 1913-1916 period-

I wrote all of this forty years ago when it was still fresh in my mind. Then I checked it with the newspapers of the time to make the dates as accurate as possible. I re-wrote it and got others to read it. It is of course possible for errors to have crept in but I am sure that I have represented the views and opinions of the principal actors correctly. Eamon De Valera, Sean T. O Kelly and Cathal O Shannon have read it and they allow me to say that I have stated correctly all that part of it that is within their personal knowledge.

[Speaking of 1916…]

I do not think that anyone who did not live in those times could realise how few our resources were or how small the material was out of which we had to build up a resistance. There is no comparison with the Ireland of today. The whole structure of living was organised against the Irish people in their own country….

There was no possible choice of weapon, very small choice of plans; the leaders had nothing but their bare hands. There never was a prospect of success. The one certainty was that it was better to be dead than to be a slave. Because they were convinced of this, they did what they could and the ultimate result has been beyond their wildest dreams.

And in a 1980’s newspaper interview:

Anyone who says that nothing has been achieved since then has not the remotest idea of what conditions were like in Ireland. A terrific amount has been done and is being done every day and more would be done if people realised that they are free to do it.

My mother had also pointed me to my grandmother’s papers, dating from the 1980’s, in the National Library in which she wrote the whole story again, although she was then in her nineties and battling illness. Along with the papers I have mentioned are the typescripts for her book, a set of taped memoirs transcribed by my sister, Barbara, the introduction to Joseph Plunkett’s Poems, published in 1916, a series of articles for the 1950’s University Review, statements for the Military History Archive on events leading to the 1916 Rising and on the War of Independence in Galway, 1920-1921, which included accounts she had collected to record both Black-and-Tan atrocities and Volunteer activities. She also wrote a series of seven talks for Radio Eireann entitled The Years of Change broadcast in 1958, articles for The Capuchin Annual, The Connaught Tribune and The Dublin Magazine, an article on her grandfather, Patrick J. Plunkett and a lengthy letter to Professor Desmond Williams on Rory O Connor and the Civil War. She corresponded and checked her information with many people including Dan Nolan, Cathal O Shannon, Frank Robbins, Bulmer Hobson, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, William O Brien, Eamon Dore, Eamon de Valera, Seán T. O Kelly, Edward Shields, Aidan McCabe, Donagh MacDonagh, Prof. F. X. Martin, Prof. Roger McHugh and Prof. Desmond Williams. She was interviewed many times in all of the national newspapers, on radio and, later, television from the 1940’s right up to her 94th birthday and some of these survive, the best being two unedited interviews in the Kilmainham Jail Archive for the 1966 programme, Portraits. There are many other small items of memorabilia which contribute to the picture, including the Deed of Family Settlement which tracks the legal origins and history of the considerable family property.

In the construction of this book I have tried to combine these sources in such a way that each element will contain the best details and the best of my grandmother’s voice which is so strong in flavour and conviction. For clarity, I reconstructed the text chronologically and inevitably this meant some small stitching on my part, but I have tried to stay with her language and accounts and in some instances I have inserted stories or details she told me or my siblings which are not written down. Because of the volume of material I had to make a selection, so my personal bias is there but influenced by my great friendship with her and I hope it serves her well enough. Accuracy had to be a primary consideration which meant constant background work to try to know and understand episodes in history. She was extremely accurate most of the time but I freely acknowledge that despite both our best efforts, inaccuracies are inevitable! Her papers in the National Library tend to have more mistakes than the other material as she was writing at speed, without reference material and already ill, but even these mistakes are usually minor.

My greatest regret throughout the process has been how little credit she gives herself, for example she does not mention a paper she gave in the Royal Irish Academy in 1916 or her contribution to the article on dyes in Encyclopedia Britannica or her volume of poetry, Magnificat, or contributing to the Book of St Ultan, or being a founder member of Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe (the masks of Tragedy and Comedy she made for the Gate theatre are now on a wall in the Taibhdhearc) and the Galway Art Club, where she exhibited for years, or making costumes for Micheál Mac Liammóir in 1928, or being responsible for Oisín Kelly deciding to become a sculptor – he was one of very many who said that she enabled them to do the right thing for their own fulfillment. When she wrote it was in order to provide a history of her times and an insight into what made her family so strange. Like many of her generation she did not write much about her own feelings and her humourous and optimistic nature does not really come through in her writing. I would like to have been able to put that in but could not in all faith do so.

We called her ‘Mamó’, one of the Irish versions of ‘Granny’, and for thirty-five years of my life I lived with her stream of stories and memories. She talked about everything from the appalling carry-on of her mother to the near misses with the Black and Tans in Galway and wanted us and everybody else to know how awful it was at the time for herself and her siblings but even more for the people she saw in such great poverty and distress. She said herself that she had almost total recall and disliked the notion that everyone in the past was virtuous and temperate as she knew many people who drank themselves to death or out of a business, families ruined by violence and waste and lives ruined by drugs. Her sense of humour never deserted her and she always contrived to end even the most savage story with a chuckle.

She did not write as much about my grandfather, Thomas Dillon, as one might expect. He was a great teacher of Chemistry and, among other things, produced the first women professors of Chemistry in Ireland. He was dedicated to the idea of university education, particularly through Irish, which he learned in jail, and thought the development of natural Irish products essential to the progress of the State, his speciality being research into the by-products of seaweed. In his personal life he could be flighty and irresponsible and one too many incidents meant that in her writings she did not give him the credit she might have done in the days when she loved and admired him so much.

When she was dying she gave me her brother, Joe’s, copy of Wolfe Tone’s Autobiography, which had been his bible. ‘You’ll understand about that’ she said and although I knew what she meant, I knew I didn’t understand, but I think I do, a little, now.

A Short Biography of Geraldine Plunkett Dillon 1891-1986

Geraldine Plunkett was the daughter of Count George Noble Plunkett (1851-1948) who was a close friend of Parnell’s, Director of the National Museum of Ireland, a scholar and internationally recognised expert in Renaissance Art. He was a member of the First Dail, being elected for North Roscommon in 1917 and the first Minister for Arts and Culture in Ireland. Her mother, Josephine Cranny was a whimsical and violent woman who made her children’s lives chaotic and unpredictable. Geraldine’s grandfathers were both builders and developers in large areas of Donnybrook Ballsbridge and Rathmines in the late nineteenth century, making their children the wealthy owners of considerable amounts of property.

Geraldine (Gerry) was born and brought up in Fitwilliam Street and in an odd selection of other houses. She was the middle child of seven children and her older brother, Joseph Mary Plunkett (Joe) was executed in 1916, being a member of the Military Council of the 1916 Rising, one of the signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and a poet. They were educated in an assortment of schools in Ireland and England and Geraldine began a degree in medicine in the new National University, changing to Chemistry where she distinguished herself but was unable to finish as she went to live with Joe in Donnybrook in 1912 to look after him. He had Tuberculosis and his health had been worsening over the years.

Joe started the Irish Theatre with Tomas Mc Donagh and Edward Martyn (also known as Edward Martyn’s Theatre of Ireland), took over the Irish Review from Padraic Colum, published books of poetry with Tomás McDonagh, became a member of the Peace Committee in the 1913 Lockout and, at the inaugural meeting of the Volunteers, he was appointed to several committees. When his involvement with the Volunteers and the IRB increased, Gerry became his aide-de-camp and got to know all the leaders of the 1916 Rising well. Some of them were already friends and most of them became very close friends. Joe talked through all his ideas and activities with her and encouraged her into understanding, not just Ireland, but also the international situation by reading and analysing newspapers and journals. He devised the military strategy for the Rising and when Connolly joined the Military Council, he and Joe worked together on the plans. Joe and Gerry moved for part of the time to Larkfield in Kimmage where everything from battalion training to poplin weaving went on. It was there that Joe brought in Michael Collins (initially without knowing him) to help Gerry with organising the family accounts.

Gerry fell in love with her chemistry lecturer, Thomas Dillon and they were to be married on Easter Sunday, 1916 in a double ceremony with Joe and Grace Gifford. When the time came Joe was prevented from marrying by the crises surrounding the Rising, so Gerry and Tom were married in Rathmines and stayed in the Imperial Hotel in the middle of OConnell St. to be available for action. From their hotel window they watched the beginning of the Rising and saw Joe for the last time when he stood outside the GPO and fired one shot into an empty tram to detonate an explosive and create a barricade. Joe sent them a message to go back to Larkfield and Rathmines to make gun cotton. They had to wait for news of events with the other friends and relations, including Muriel Mc Donagh and Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, through terrible times. They were in Rathmines on May 3rd when they heard that Joe was to be shot in the early hours of the next morning.

Her brothers, Jack and George were also condemned to death, but their sentences were commuted and they were sent to jails in England. Her parents were arrested and jailed, her mother in Mountjoy and her father in Richmond Gaol, for a couple of months and then exiled to Oxford until her father came back for the 1917 election, at which time Gerry was pregnant with her first baby. In 1918 her husband (then secretary of Sinn Fein) and her father and brothers were again arrested and sent to English jails while she was having her second baby. In 1919 her husband (just released from Gloucester Gaol) was appointed Professor of Chemistry in Galway and it was there that she was sworn into the IRB by a representative of her old friend, Michael Collins. As a result of their part in the War of Independence in Galway, she and Tom and their children were constantly on the run in those years (they lived in about fifteen houses), raided by the RIC and the Black-and-Tans and Gerry was jailed in 1920. A question was asked about her in the House of Commons and her release was ordered.

Her eldest sister, Mimi died of TB in 1926 and her second sister Moya, of cholera in 1928, both needlessly, she felt. Her brother, Jack was interned for IRA activity during the Second World War and he never fully recovered from the effects of hunger strike and depression. George died after a fall from a pony and trap in 1944. Her sister Fiona was engaged three times but never married and lived with her mother, who tormented her. Gerry put this propensity for tragedy and disaster firmly at her mother’s door and explains how and why in her memoirs. Her mother, Countess Plunkett died in 1944 and her much-loved father, Count Plunkett, who remained a member of “The Second Dail” until he was nearly 90, died in 1948. He was given a full state funeral and buried in the Republican plot in Glasnevin.

Through the twenties and thirties her family’s story was tragic, turbulent and often funny but her extraordinary resilience, intelligence and sense of humour kept those around her from disintegrating and enabled her five children to lead imaginative lives and become celebrated in their own right – Moya, the doctor, counsellor and artistic needlewoman, Blanaid, the solicitor working in women’s rights, structuring law for the sale of apartments and co-founder of the first professional Ballet Company in Dublin in the 1950s, Eilis Dillon, the well-known author of many novels, detective stories and children’s books, Michael Dillon, the pioneer in agricultural journalism in all media and Eoin Dillon, the international hotelier, manager of, among others, the Shelbourne and Gresham Hotels in Dublin and the London Tara Hotel. Her husband, Professor Thomas Dillon, was a leading teacher and researcher in the world of chemistry who broke new ground in the uses of alginates and was a pioneer in the development of Irish universities. She herself contributed significantly to Galway and its people, particularly in the Arts, campaigning for the preservation of stone artefacts in the town, being a founder member of Galway Arts Club and Taidhbhearc na Gaillimhe and a riverside walk there, for which she campaigned, is dedicated to her.

She had a vivid and accurate memory of her own life and childhood and a great store of information on her forbears and ancestors. From the nineteen-forties onwards she wrote her story several times and in different ways: a set of copybooks in an informal style, a set of radio talks, broadcast in the fifties, articles for University Review, television interviews, typescripts for a book and another set of notebooks, now in the National Library, written in the nineteen-eighties when she was over ninety and still an active thinker. All through her life she corresponded with the surviving protagonists of the 1916 to 1923 era in order to check details for historical accuracy and she read most of the books that were published in the area. She has a blunt and quirky style and a strong desire for the truth to be told, to avoid her pet hate, the sentimentalising of “the good old days”.

The only serious flaw in her material is that she does not reveal herself as the humourous, generous and outstandingly gifted person she really was. Like the sculptor, Oisin Kelly, many thanked her in her old age for some indispensable moment of encouragement she had given them.

Honor O Brolchain